Hajj: The Pilgrimage To Mecca

Here we come, O Allah, here we come!

Here we come. No partner have You.

Here we come! Praise indeed, and blessings, are Yours — the Kingdom too!

No partner have you.

Image by flickr

This Talbiyah, recited by more than a million Muslim pilgrims in December 1973, marked the formal beginning of our pilgrimage. Etched in memory was the scene at the airport in Beirut, where we waited all night for our flight to Jidda in Saudi Arabia. My father and I, each clad in two pieces of seamless white cotton terry cloth, bareheaded and wearing sandals, and my sister Aisha, with only her face and hands exposed, were among hundreds similarly clad.

How spoiled we were! The thought of the African herdsmen who had walked much of the way, and the Indonesian peasant who had invested his life savings in making this pilgrimage by sea, shamed us into thanking god for the ease with which we were performing our hajj.

At dawn we boarded: “First-class passengers, then tourist class…” How awkward that there should be such a distinction on this journey. Trappings of class here were more a cause of embarrassment. My father remembered savoring the feeling of quality on his first pilgrimage 25 years earlier, when he rode from Kuwait in the back of a truck.

Now in a state of ihram (restriction) — forbidden to clip our nails, cut our hair, hunt, argue or engage in sexual activity — we were eager to join out brethren converging on Mecca from all over the world. There we would perform a major duty in our religion: the pilgrimage to Kaaba, originally built, Muslims believe, for the worship of God by Abraham and his son Ishmael, ancestors of our prophet Muhammad.

The annual pilgrimage, instituted by Abraham, was continued by succeeding Arab generations, for it brought wealth and prestige to Mecca. Pagan practices, however, were gradually introduced until the religion of Islam, with its dedication and submission to God, came in the seventh century A.D., restored the hajj to its purity and made it a deeply spiritual journey.

In two hours we were in Jidda, and by late morning we began the 45-mile drive to Mecca. Busloads of pilgrims were around us, and what a variety of features — Asian, black, white and all the blends brought by generations of intermarriage.

On the way we stopped at the Mosque of Hudaybiyah, site of a treaty marking the political turning point of Islam in its battle for survival in the seventh century. Here Muhammad concluded a truce with Quraysh, the polytheistic inhabitants of Mecca among whom he was reared and to whom he first delivered his message: God is One.

The Quraysh had responded with unrelenting persecution, forcing Muhammad to emigrate from Mecca — the Hegira, A.D. 622, which begins the Muslim era. The treaty halted the battles waged against the Prophet and his new town, Medina, more than 200 miles north, allowing him and his community to practice their faith in peace.

Continuing on our way, we passed a white pillar that marked the entry into the sacred territory, a circle around Mecca in which no wild animal may be hunted. Chanting the talbiyah, our excitement mounting, we came to the city’s outskirts. In one of these buildings, the kiswa, the embroidered black cloth covering the Kaaba, is made anew each year.

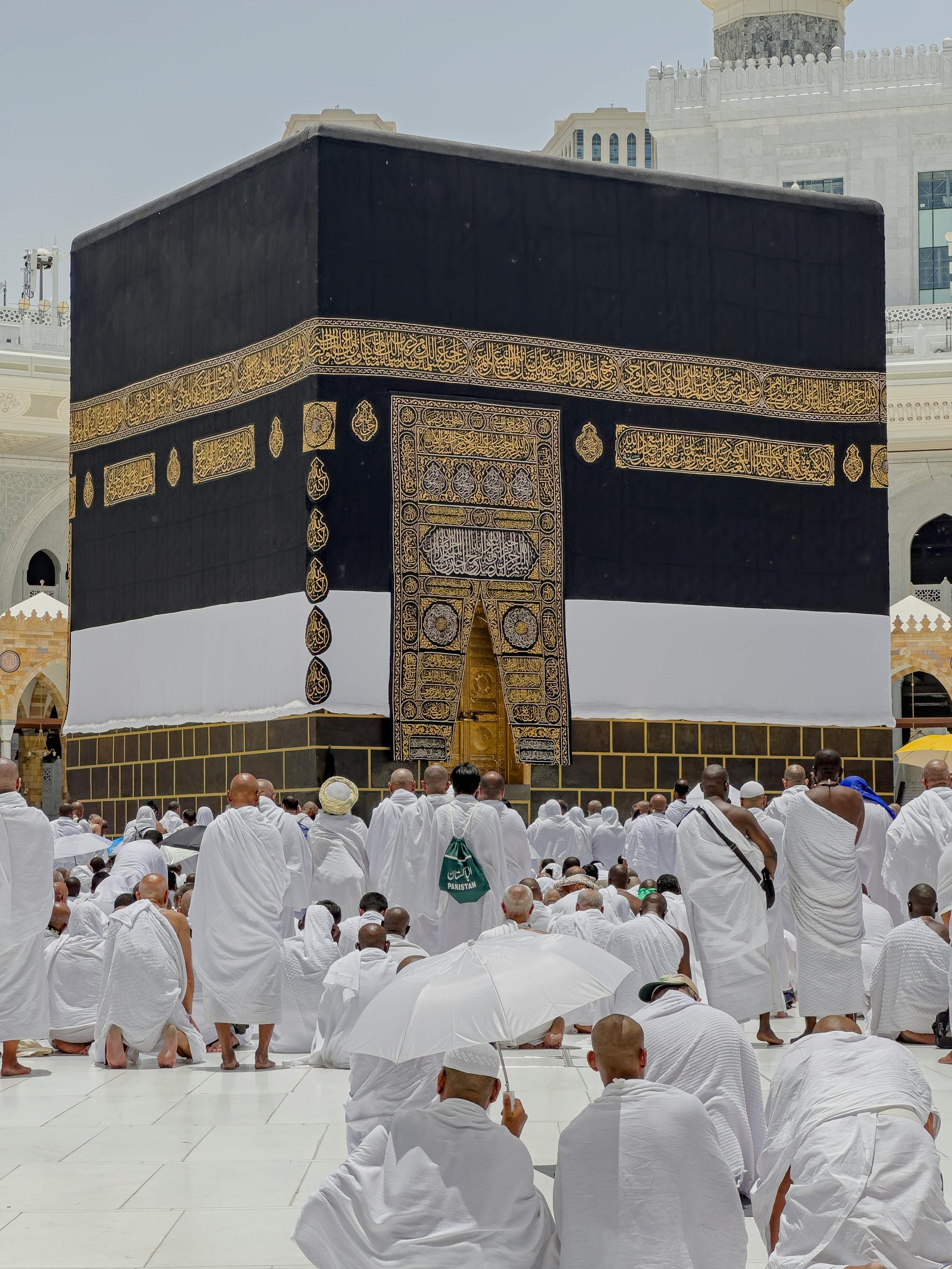

Finally we were in Mecca, Islam’s holiest city, crowding a barren valley walled by harsh hills. Accompanied by Adeeb Tilmissan, a courteous young Saudi student assigned to us by our host, the Muslim World League, we drove through teeming shop-lined streets to the sacred Mosque to perform the tawaf, the prescribed seven counterclockwise circumambulations of the Kaaba. Entering through the gate of Peace, we were met by a hum of chanting. In the middle of the mosque’s large open court our eyes fell on the Kaaba, majestically towering over a sea of humanity.

It is impossible for any pilgrim to forget that first sight of the black draped shrine. Five times daily in our prayers, from whatever part of world we are in, we face toward the Kaaba, longing for the moment we can cast our eyes on it and touch it.

Each pilgrim reacts to seeing the Kaaba in his own way. In my father’s first experience he felt dizzy. My mother clung to his arm, trembling and sobbing. This time my sister shuddered as if an electric current had shot through her, and I was speechless, struck by deep feelings of sweet tranquility.

Caught up in the ecstasy of devotion around us, we recited together:

O lord! Grant this house greater honor, veneration and awe: and grant those who venerate it and make pilgrimage to it peace and forgiveness

O Lord! Thou art the peace. Peace is from Thee. So greet us (on the Day of Judgment) with the greeting of peace.

Why this veneration of a stark cube like building of gray stone? It is not a striking piece of art, nor is it adorned with precious stones. And no Muslim endows it with power to benefit or to hurt. The Kaaba is the House of God, dedicated to His worship by Abraham. Near it the Prophet Muhammad was born about A.D. 570. Forty years later the archangel Gabriel descended with the revelation of the truth — that there is but one God — calling Muhammad to cleanse the Kaaba of idols. And here, eight years after his emigration from Mecca, the Prophet triumphantly yet humbly returned to see those idols toppled at his beckoning and the purified Kaaba rededicated to the worship of the one God.

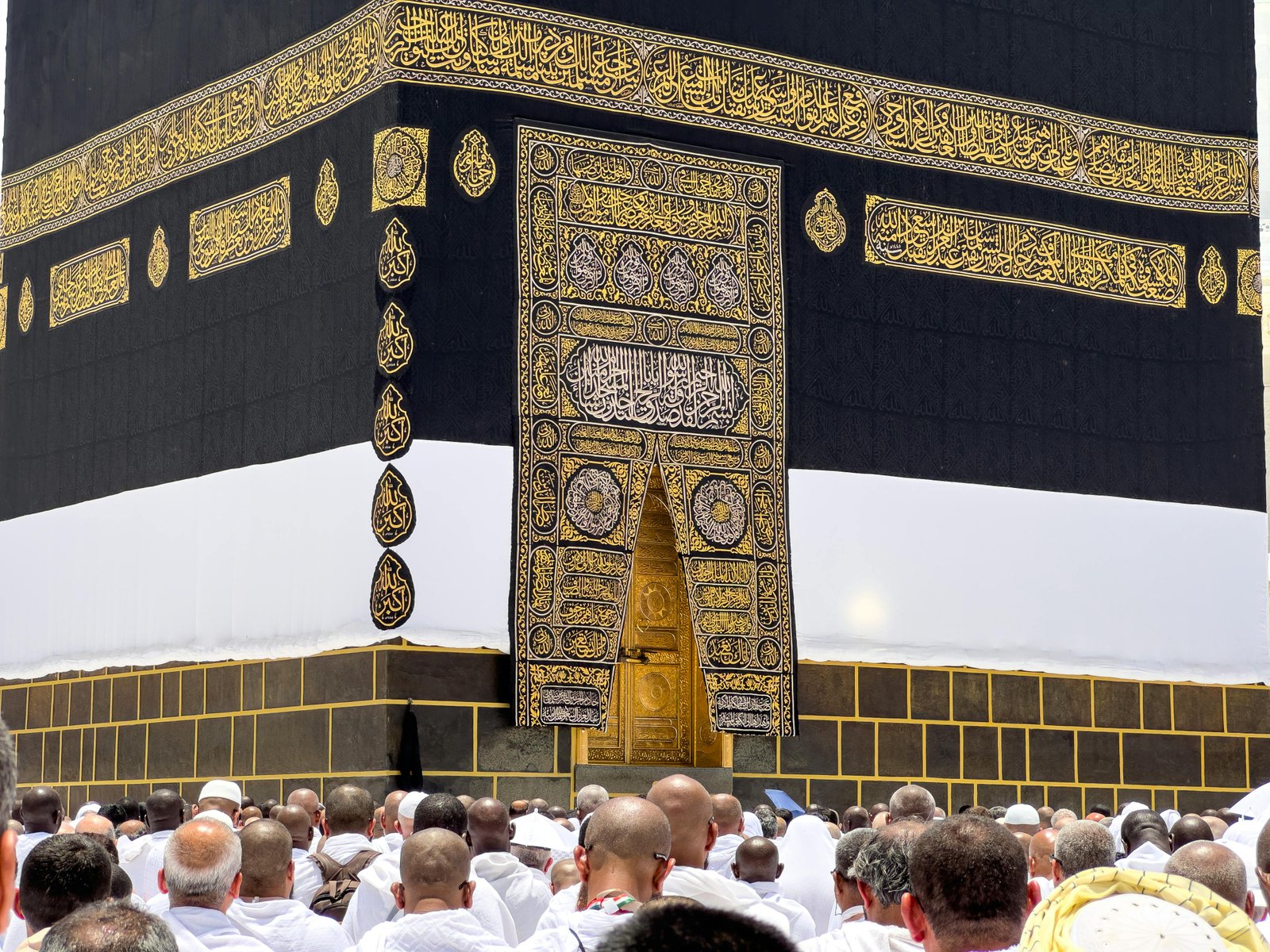

We plowed through the crowded court toward the black stone. This sacred rock, 12 inches in diameter, is set in silver in the corner of the Kaaba. The only remaining relic from the original building of Abraham, it is the starting and end point of the tawaf (the circumambulation around the Kaaba). Pilgrims are eager to touch or kiss it, as it represents the right hand of God, with whom they are renewing their covenant. Reading the golden Quranic lettering embroidered on the Kaaba’s black cover reminds us of its original builders, Abraham and Ishmael, and their prayers to God to raise from the area a messenger of peace, learning and wisdom.

At last we came close, but the crowd was too thick for us to touch the stone, except Aisha, aided by the police officer in charge. Swept along by the human tide, we kept chanting prayers, struggling to touch the stone or the Kaaba whenever possible.

Coming opposite the black stone on each circuit, we raised our right hands to it and recited: “In the name of God; God is the most great!” The Kaaba loomed over us as if it were an ear of God absorbing the earnest prayers of His human creatures. Like subjects appealing for their sovereign’s favors at the foot of his throne, we circled our Lord’s House, shedding tears seeking blessings and mercy and yearning for His Company in paradise.

On completing the tawaf rituals, we went to drink from the Well of Zamzam, with its rich mineral water with which Ishmael and Muhammad had quenched their thirst.

Ishmael and his mother, Hagar, the tradition goes, were left alone in the desolate valley by Abraham with only dates and water, which were soon exhausted. Seeing her infant writhing in thirst, Hagar desperately searched everywhere for water. She had asked the departing Abraham, “Has your Lord instructed you to leave us here alone?” When Abraham answered affirmatively, she said, “Then God will not abandon us.”

God did not abandon them. Zamzam was revealed to them, and beside it Abraham and Ishmael in time built the House of God, and the town of Mecca grew up around it.

After the greeting tawaf, performed on arrival in Mecca at any time of the year, pilgrims proceed to the ceremony of the sa’y, making seven trips between the hills of Safa and Marwah, now inside the mosque. This ritual reenacts Hagar’s search for water before she was led by an angel to Zamzam. During the seven journeys of the sa’y, a pilgrim recites prayers, his heart closely in communication with God.

Whether they arrive early or late during the 70-day pilgrimage season, which begins annually with the start of the 10th month of the Muslim lunar calendar, pilgrims spend the eve of the ninth day of the 12th month in the village of Mina, four miles east of Mecca. Following the practice of the Prophet, they rest before the day of the “standing.” During this high point of the hajj rituals, pilgrims stand on the Plain of Arafat, eight miles farther east, greeted by the bright colors of sunrise.

Pilgrims crammed cars, buses and trucks and rode on the backs of camels and donkeys. Often those on foot seemed to make the fastest passage. By noon all would make it to the hot desert plain, all clad in the same simple attire, rulers and subjects, rich and poor, men and women, black and white.

It was a scene to last in memory: a million and a half people assembled for the day on this barren, rocky plain, leaving all wealth and fame behind, praying for salvation and for our brethren’s deliverance. Thus we reinforced the sense of equality before the Lord and reminded ourselves of the day to come when all will be raised and gathered for accountability, leading to eternal bliss or affliction.

Some pilgrims climbed to the spot where the Prophet, from the back of his camel, delivered his farewell sermon. In it he reiterated some of the basic teachings of Islam and bore witness to his companions that he had given his message and fulfilled his burden of prophethood. Three months later, in Medina, A.D. 632, he died.

Shortly after the sunset the reverse rush toward Mecca began. On the way back to Mina pilgrims halt for the night at Muzdalifah. There they offer prayers, as the Prophet did. And there they collect pebbles to throw at the three “Satan’s stoning points” in Mina during the following days. These pillars symbolize the forces of evil, and casting stones at them symbolizes our lifelong struggle against evil.

On the 10th day of the month pilgrims celebrate the Eid al-Adha (Festival of Sacrifice) — which marks the end of the pilgrimage season — by sacrificing an animal, thus commemorating Ishmael’s deliverance.

We drove from Muzdalifah to Mecca soon after midnight, halting briefly at Mina for the first part of the stone-throwing ceremony. Then we returned to the Sacred Mosque to perform the post-Arafat tawaf in the same way we made the greeting tawaf, followed by the sa’y ceremony. Then each of us had a lock of hair clipped, symbolizing the end of ihram.

Afterward, we could have returned to our room, had a shower and resumed our regular clothes, but we decided to stay in the Sacred Mosque until dawn, to join the Eid prayer congregation.

We stationed ourselves on the balcony overlooking the Kaaba as throngs began to fill the vast court of the Sacred Mosque. I sat by the railing, reciting the Quran as the rapidly increasing crowds of pilgrims flowed under the bluish glow of light. I could not discern faces or heads, only a sea of human waves revolving around the gracefully draped House of God.

Hypnotized by the scene, my mind floated over the immense influence of the humble man behind this spiritual fervor, whose teaching has molded the daily lives of these multitudes, giving them spiritual and moral guidance, certainty and comfort and drawing them here from all corners of the globe.

I pictured the Prophet kneeling in prayer inside the Kaaba, cleared of the idols that had desecrated it. I felt as if my eyes penetrated those very walls before me, surveying the empty expanse within, gold-and-silver lamps hanging from a ceiling resting on three wooden columns. Would that I had the privilege of praying under that roof, prostrating myself on the marble floor. Only on rare occasions is the Kaaba opened, notably for its ceremonial washings, which is attended annually by the king of Saudi Arabia himself.

What is it that impels the Muslim to make this journey involving great sacrifice, hardship and cost, yet doing so ardently and lovingly? What meaning do the rituals have?

We each carry within our hearts a divine element. Torn from the womb of existence and ushered, crying, into this world, we spend all our energies in the pursuit of a state of happiness. This restless, incessant drive is no more than that divine element within us seeking its origin.

The joy of Islam lies in its recognition and fulfillment of man’s various needs. Unburdened by and innocent of the sin of any other, we are encouraged to pursue our material, emotional and intellectual urges and are rewarded by God for fulfilling them. Yet, we must not forget our origin, God our Creator, unto whom will be our return. Toward this end we perform ritual obligations called the Five Pillars of Islam: belief, prayer, almsgiving, fasting and pilgrimage.

These embrace the recitation of shahadah, confirming our belief in God and His angels; in resurrection for final judgment; in God’s messengers, beginning with Adam and concluding with Muhammad; and in his sacred books, including the Torah, the Psalms, the Gospel and the Quran, the word of God revealed to Muhammad through the archangel Gabriel.

They also include prayers five times daily in which we face the Kaaba wherever we may be and, without intermediary, pray directly to God, kneeling and prostrating in humility; the giving of alms, 2.5 percent of our income and savings, as an expression of sympathy to the poor and sharing in God’s blessings; fasting during Ramadan, the ninth month of the lunar calendar; and making this pilgrimage in which the Kaaba, focal point of Islam and symbol of our unity, becomes immediate and touchable.

In these common beliefs and observances, simple and clear, a Muslim feels united with his brethren in faith, now more than three-quarters of a billion worldwide.

He is also conscious of a common religious heritage with Judaism and Christianity, the other great monotheistic faiths that rose amid the deserts of the Middle East. For to a Muslim, Islam is God’s revelation made to Adam and Noah; the religion revealed to Abraham and Moses; the religion of David and the Prophets of Israel, and of Jesus and the Twelve Apostles. For the final time, in its purity, the true religion was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad.

A Muslim yearns to escape, at least once in a lifetime, from the conflicts and vagaries of daily life to the birthplace of his Prophet and the House of his Lord. There he seeks, with his brethren, spiritual nourishment and deliverance. The pilgrimage symbolizes the return to our origin. We taste the joy of this return, and that drive within our hearts is somewhat contented and fulfilled.

Divine wisdom selected the arid region of Mecca, stripped of all botanic luxuriance, purely as a focus of faith. God commanded Abraham to take his infant son Ishmael and leave him with his mother in this desert valley. On a later visit, the Quran tells us, Abraham was commanded to sacrifice him, and here Ishmael was saved at the last moment, a sacrificial ram being substituted. Here Abraham and Ishmael raised the first Kaaba. The rituals of pilgrimage recall these events, and the austerity of this site underlies its sacredness.

We cannot go on pilgrimage and expect to enjoy a comfortable vacation, pleasant scenery, good food and entertainment. We are never far from God wherever we may be. But God chose this point purely for His worship, and we are excited to have transported ourselves to this point purely for His sake.

Soon there was no more space in the mosque. “Allahu akbar! — God is most great!” came the call to prayer. The flow around the Kaaba ebbed to a stop. The human particles formed concentric circles around it, and the hum of chanting melted into silence. All I could hear was the distinct voice of the imam leading the dawn prayer, the rustle of clothes as we performed our prostrations, and the echo in my heart:

“O God! Let this not be the last time we pray before the Kaaba!”

Article source The Huffington Post