The Hajj Is One Journey We All Need to Understand

You don’t have to go round it seven times, but you almost feel you should. You almost feel, when you go into what used to be the reading room at the British Museum, where Marx, and Kipling, and Orwell used to work, and hear the wailing of a human voice that millions hear as a call to prayer, as if you should swap your jeans for a tunic. You almost feel you should shave your head. You almost feel like shouting “Allahu Akbar.”

Image by flickr

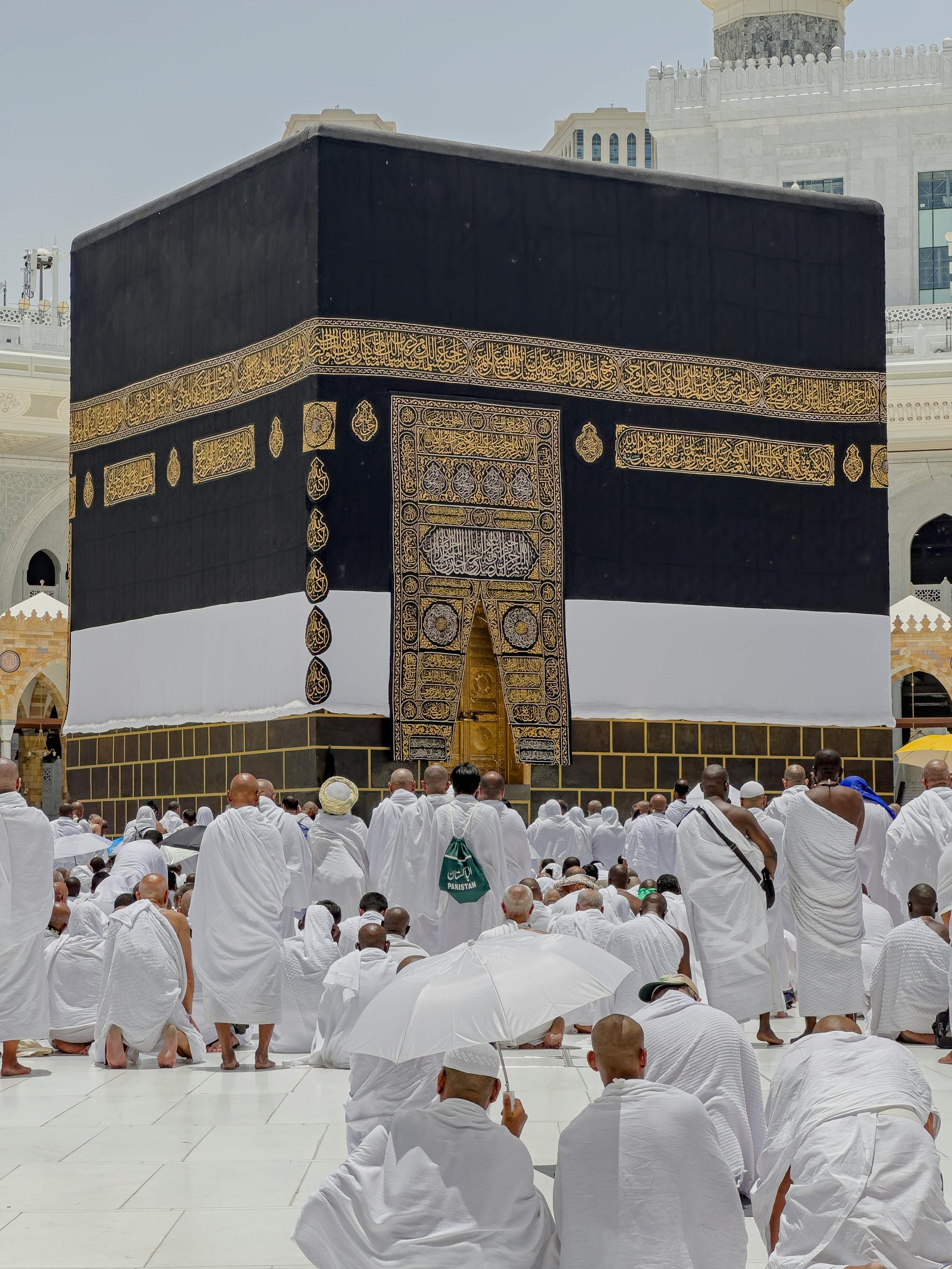

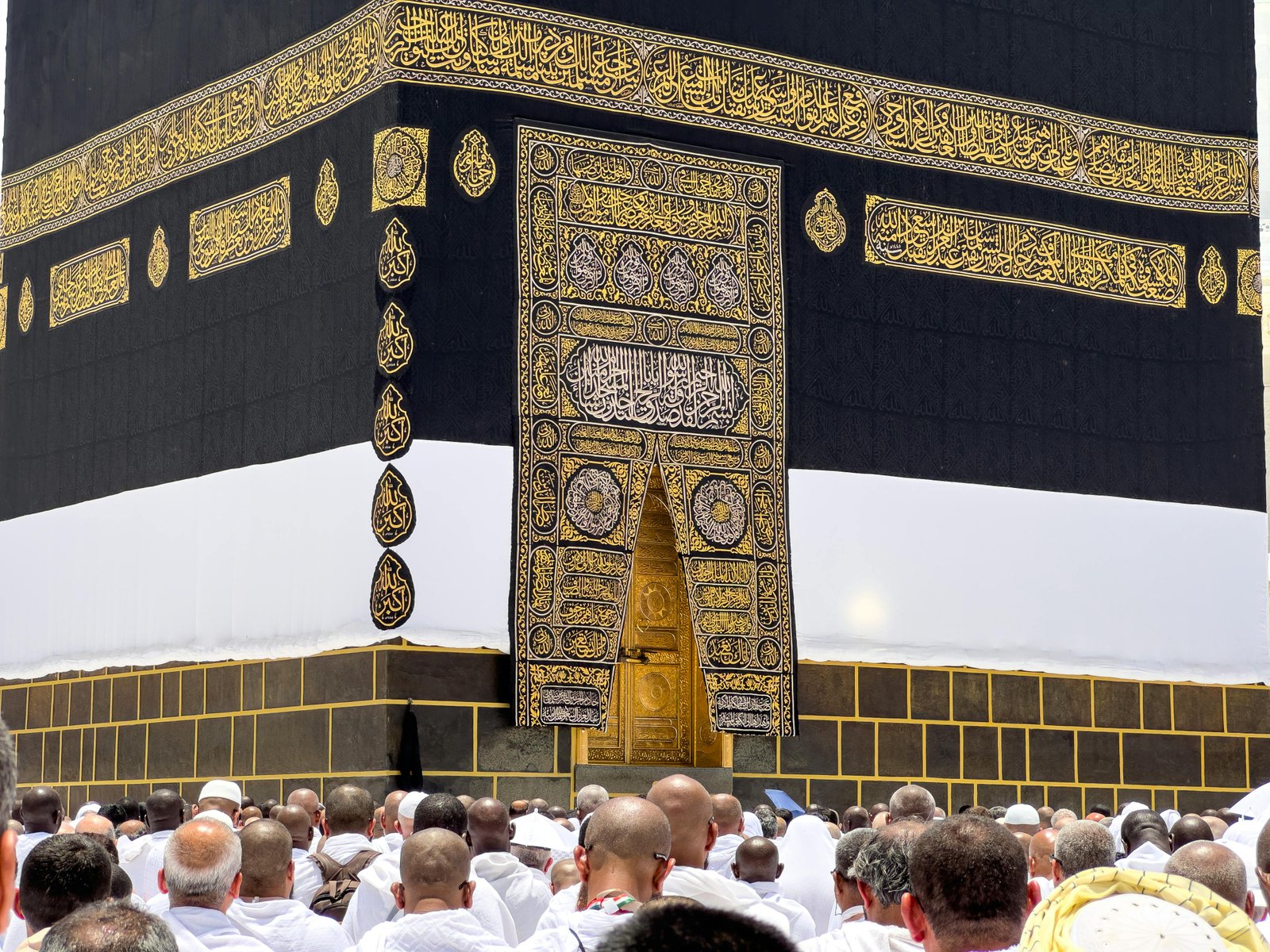

You feel this because when you walk in to the Hajj exhibition at the British Museum, which is the first exhibition ever to be put on about the journey Muslims are expected to make, you see that so many people have felt that these were the right things to do. You see them in the photos at the start: people who don’t, from a distance, look like people, but who look, instead, like dots. You see them in a film later: more people who look like dots, swirling round a big black block. And you see them in a glass cabinet: tiny splinters of metal massed round a big black magnet, tiny splinters that look like the people who look like dots.

You see, in the photos of travel agents, and of people waiting at airports, and hunched over trays on planes, that some people who have made this journey have travelled a very, very long way. They’ve done this, by plane, even when the place they’re going to is thousands of miles away. And they’ve done this long before there were planes. They’ve done this even when they’ve had to travel thousands of miles on a camel, or by boat, or on foot. They’ve done this because a man they believe was a prophet told them they should.

What you see, in the beautiful old maps, and the illuminated manuscripts, and ancient Korans, and in the guides to the rituals of the Hajj, and the pictures of pilgrims, and the embroidered textiles that were used to cover things that people thought were holy, is the power of something that has lifted people out of their lives. It has, for more than 1,000 years, made them leave, sometimes for weeks, sometimes for months, their families, and their homes, and everything they know, and taken them to a place where everything is new. It has taken them to a place where people all wear the same things, and do the same things, and say the same words. And where, in wearing, and doing, and saying these things, they feel both smaller and bigger. They feel smaller because they’re just one tiny dot in a swirling mass of dots, but they feel bigger because that swirling mass of dots is their family.

You can’t see the granite milestone, from the route from Baghdad to Mecca named after the woman who kitted it out with resting stations and wells (which, in the eighth century, not all that many women had the money to do), or the jewels worn by some of the pilgrims who travelled on that route, and not feel that this force, which drew people away from their lives and homes, and through deserts where they might die, must be really quite strong. You can’t see the pictures of the Africans, and the Turks, and the Indians, and the Uzbeks, and the Malays, who all made that journey, even though they didn’t have much money, and know that quite a few of them died in the process, or in the crush when they got there, and not think that this must, in fact, be one of the most powerful forces the world has ever seen.

You might find yourself thinking about the journeys that people who didn’t make this journey have made. You might think about how some people wanted to climb mountains, or run marathons, or sail, single-handed, across seas. You might think of the people who starve in spas. You might wonder why it was that people felt that they wanted to escape from their lives, or go on long journeys, or make a very, very big effort to do something they wouldn’t normally do, and you might decide that it didn’t really matter why they wanted to do it, but that they always had, and always would.

You might think, when you saw the little dots swirling round the big, black block, and knew that they were following a complicated set of rules that were set out in a book, as if they were playing a complicated game, that there was something a little bit sinister about three million adults all following complicated rules, in a way that made it clear that they didn’t think they were playing a game. You might think it was a little bit sinister in the way that plaster casts at Christian shrines were a little bit sinister. But you might also think that it didn’t really matter whether or not you thought the rules were sinister, or the shrines were sinister, because the rules and shrines were probably here to stay.

You might decide that, since about a quarter of the world’s population was now Muslim, and two and a half million people in Britain, and that that number was going up, it was probably a good idea to try to understand a bit more about the faith that made them travel so far. And that this journey, round this museum, which makes you think of all the journeys human beings have ever made, is a very, very, very good place to start.

Article source The Huffington Post